|

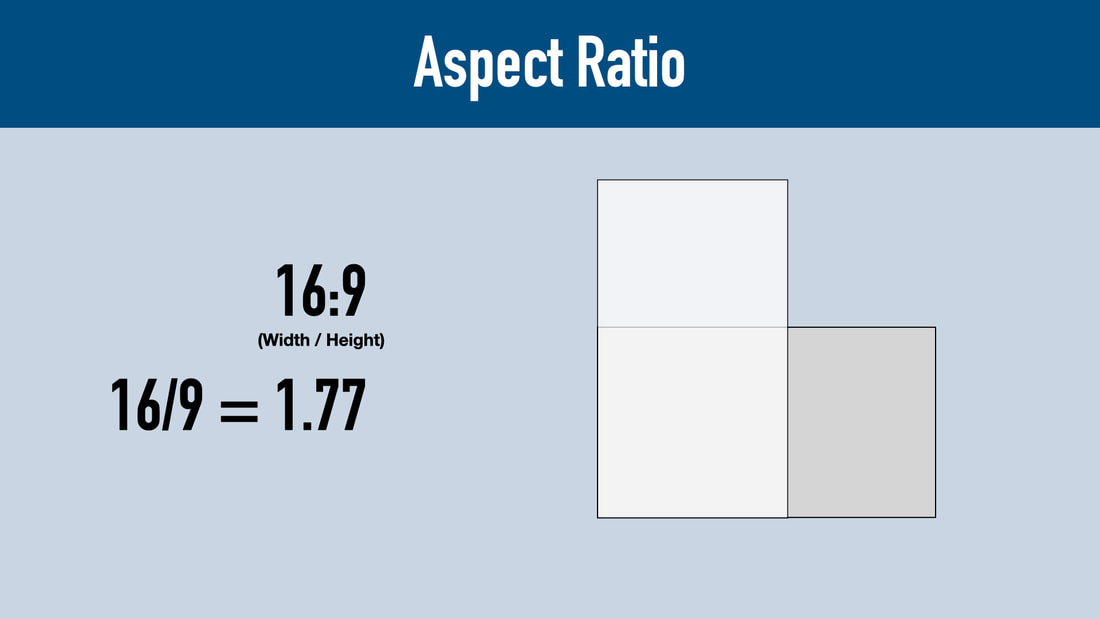

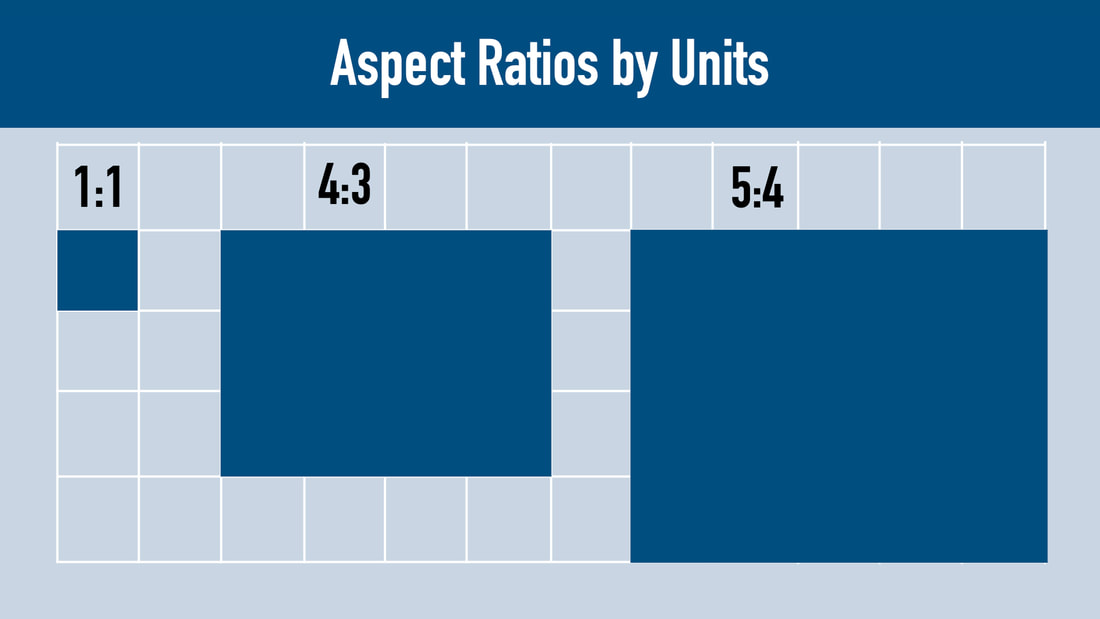

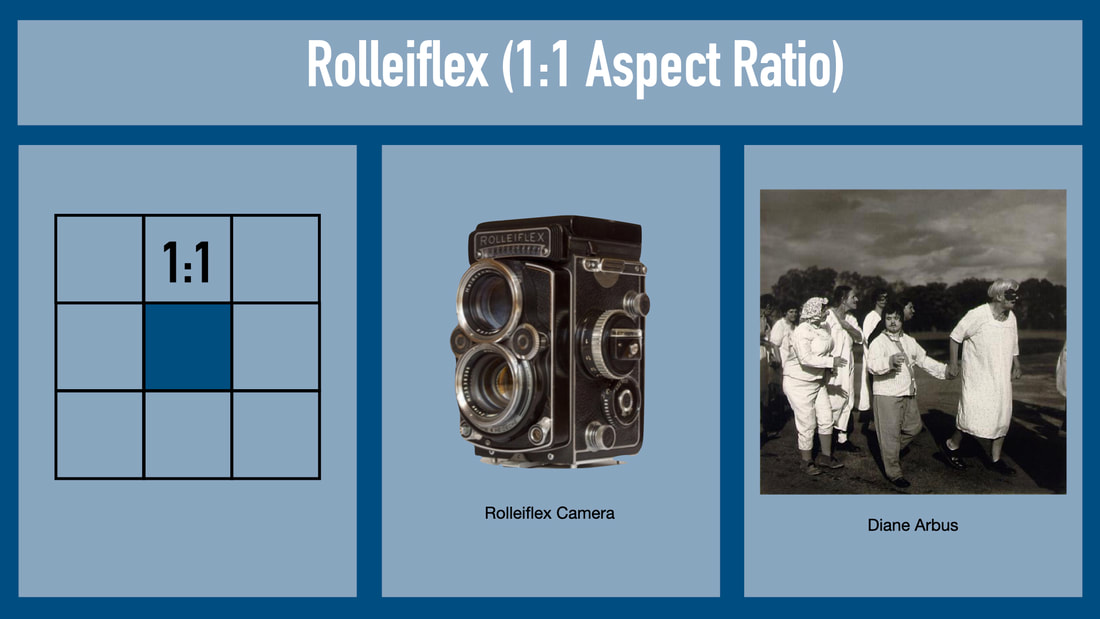

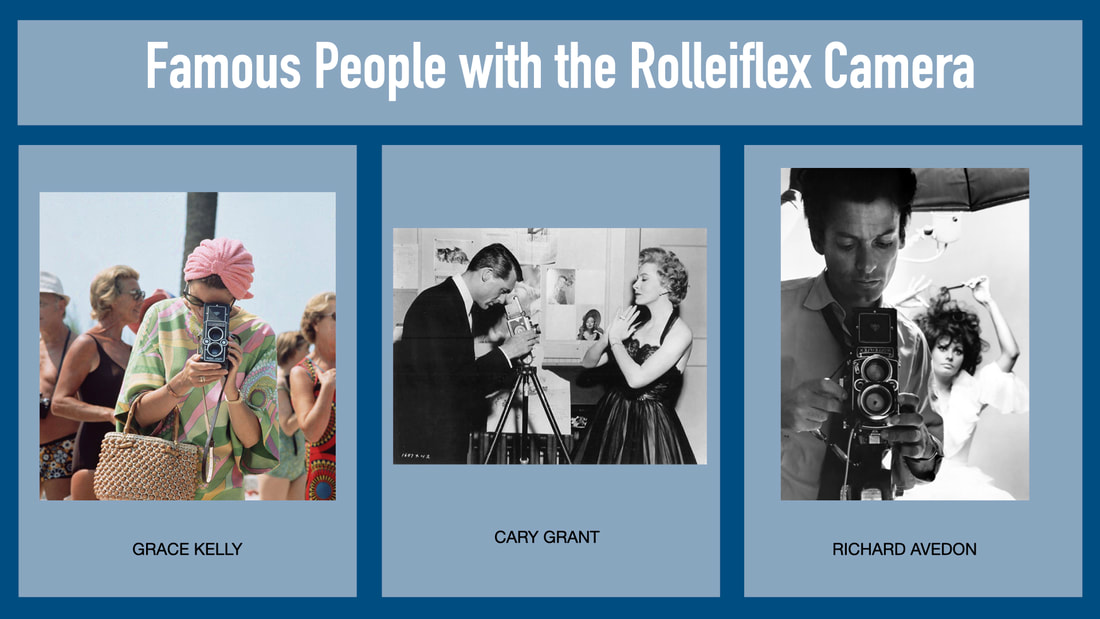

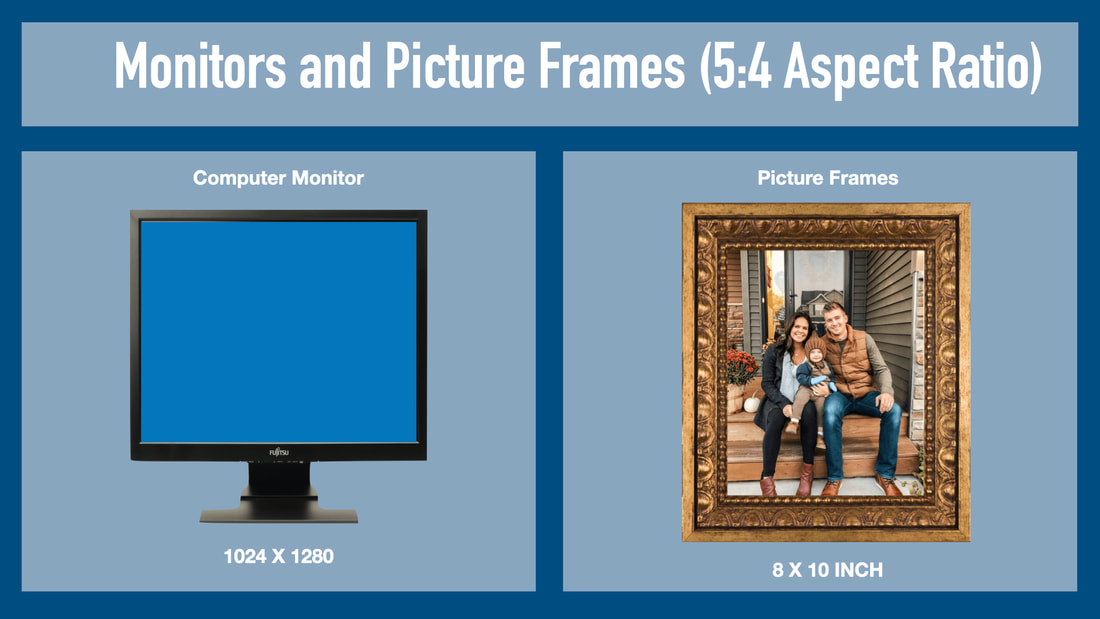

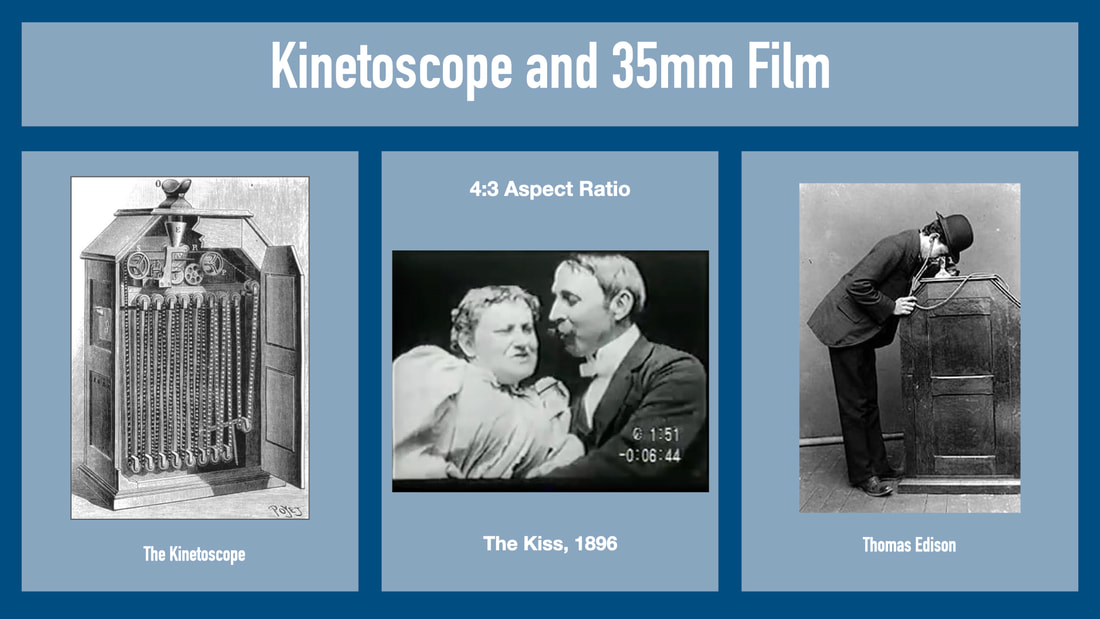

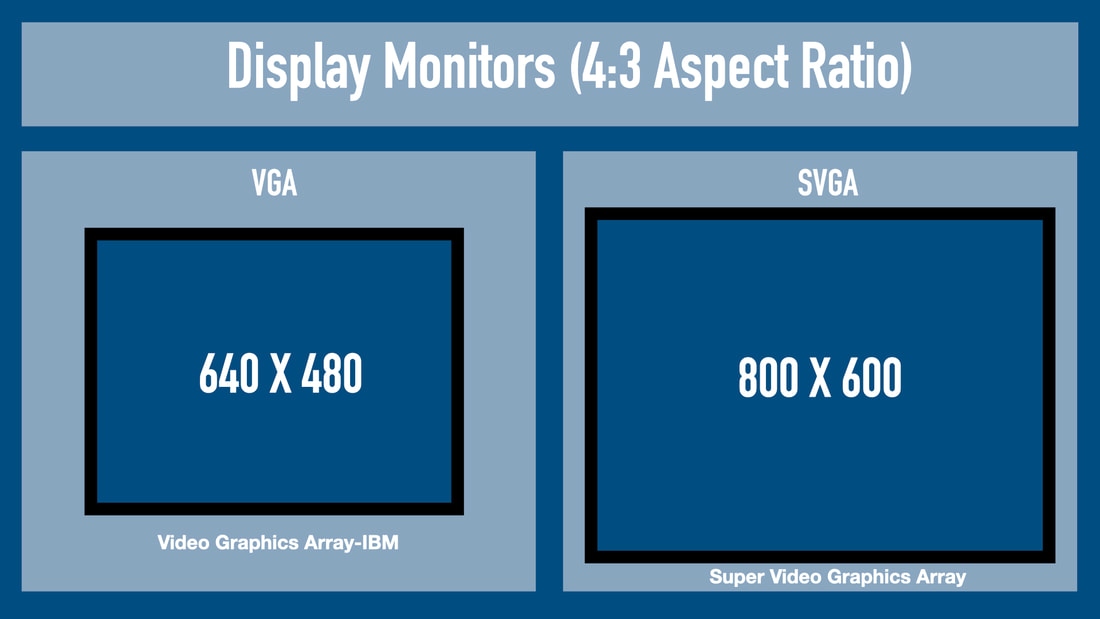

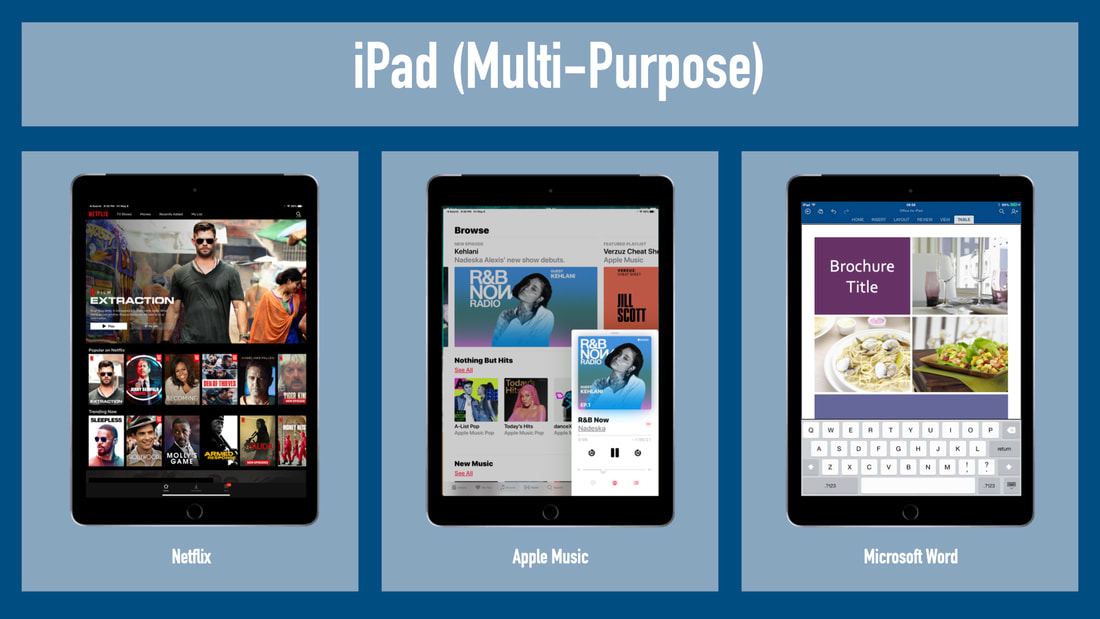

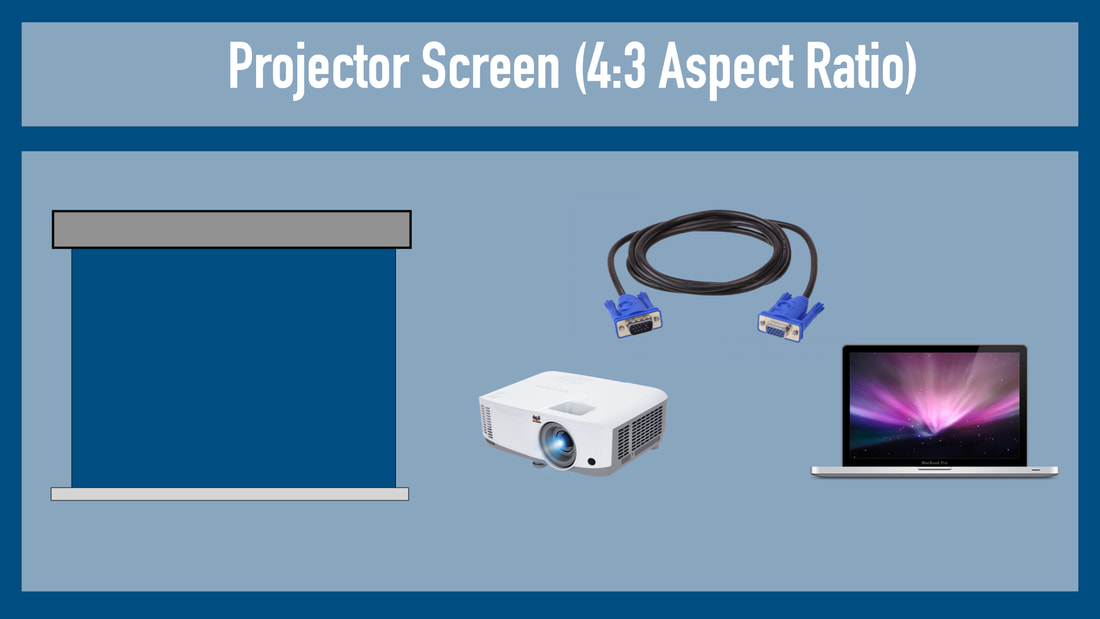

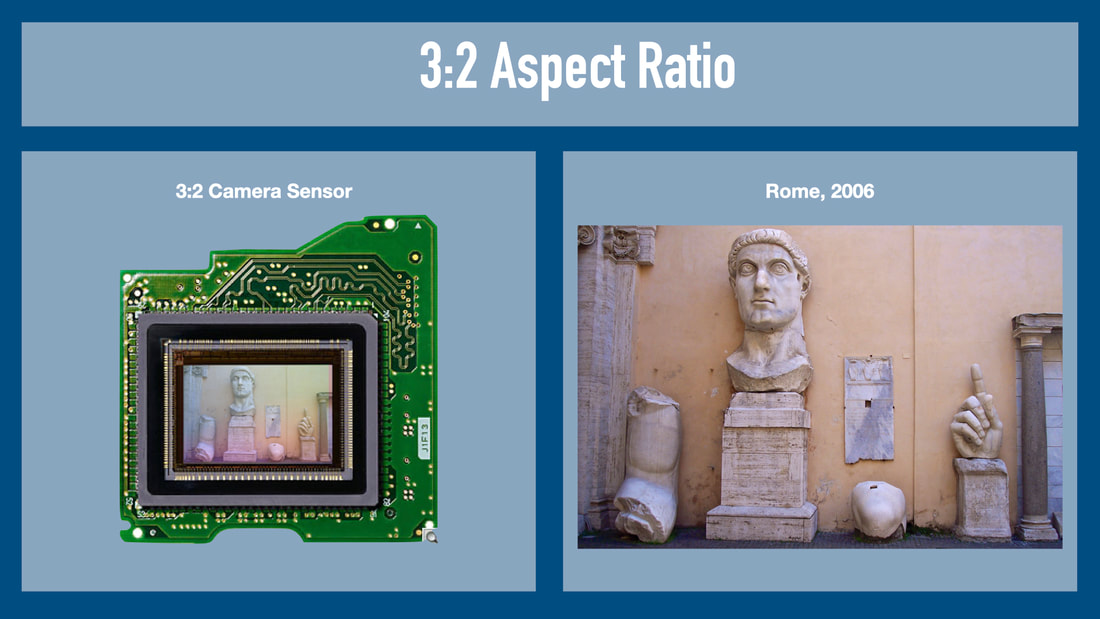

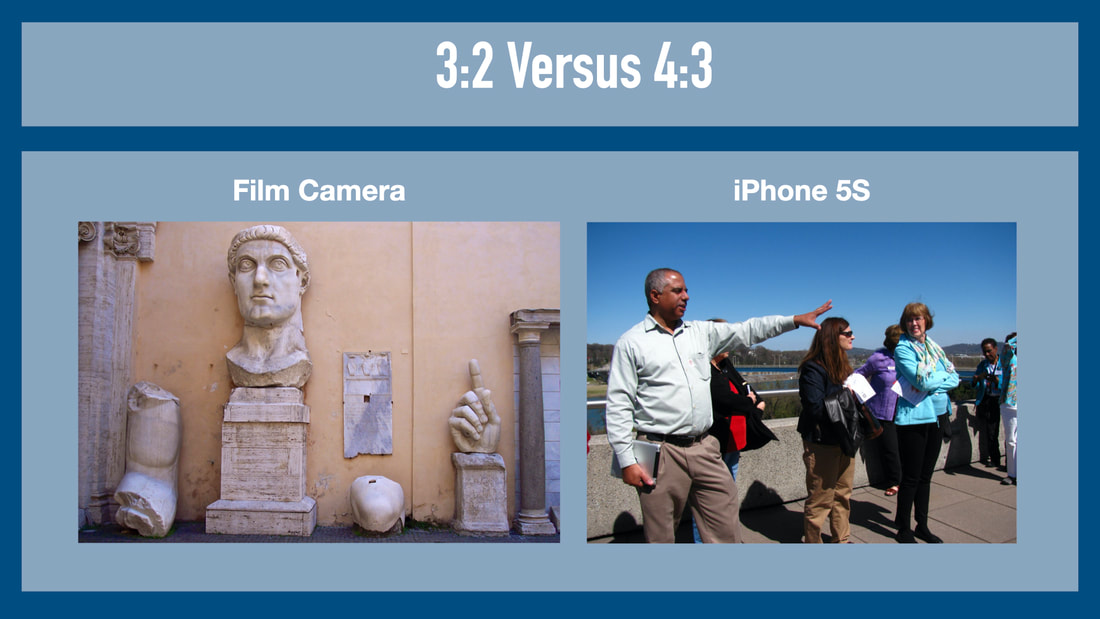

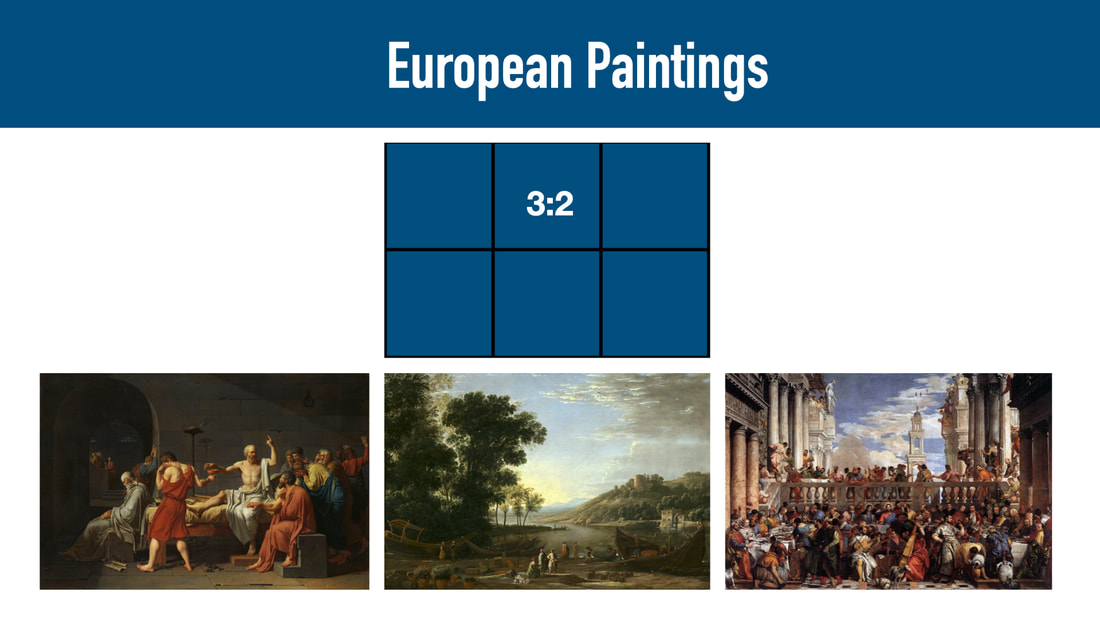

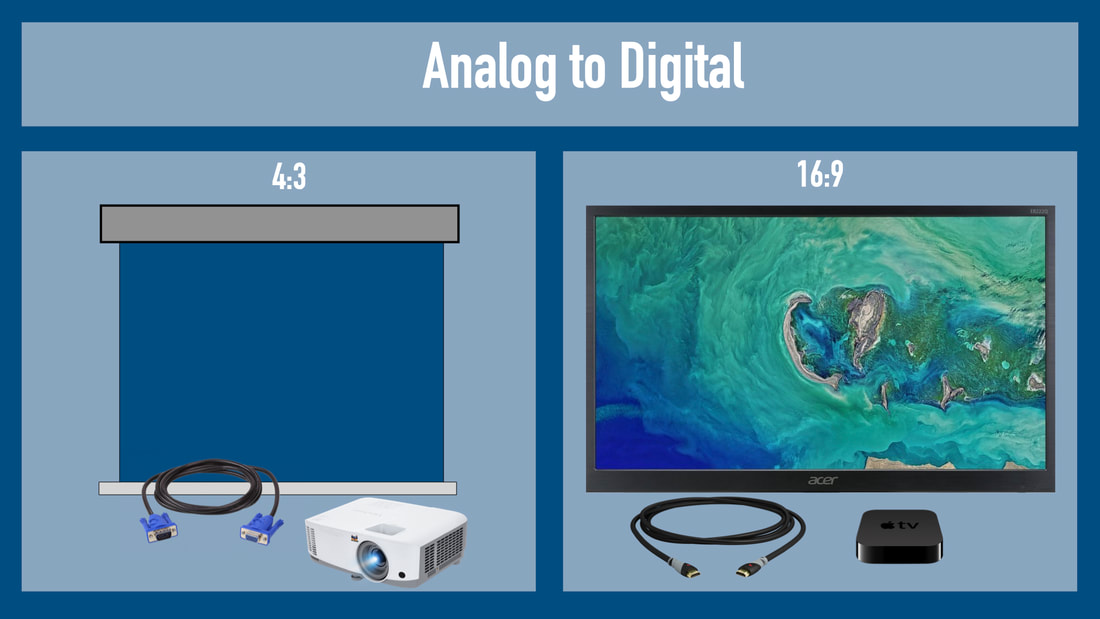

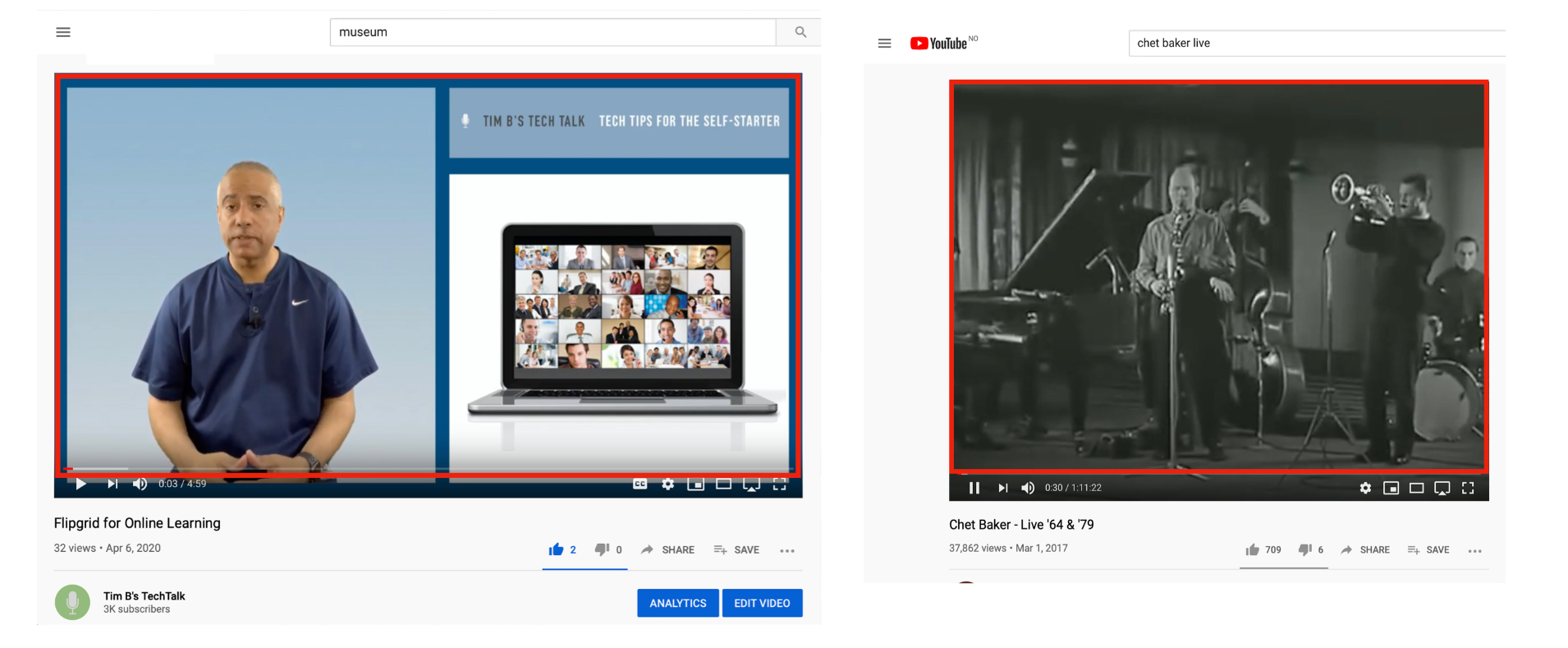

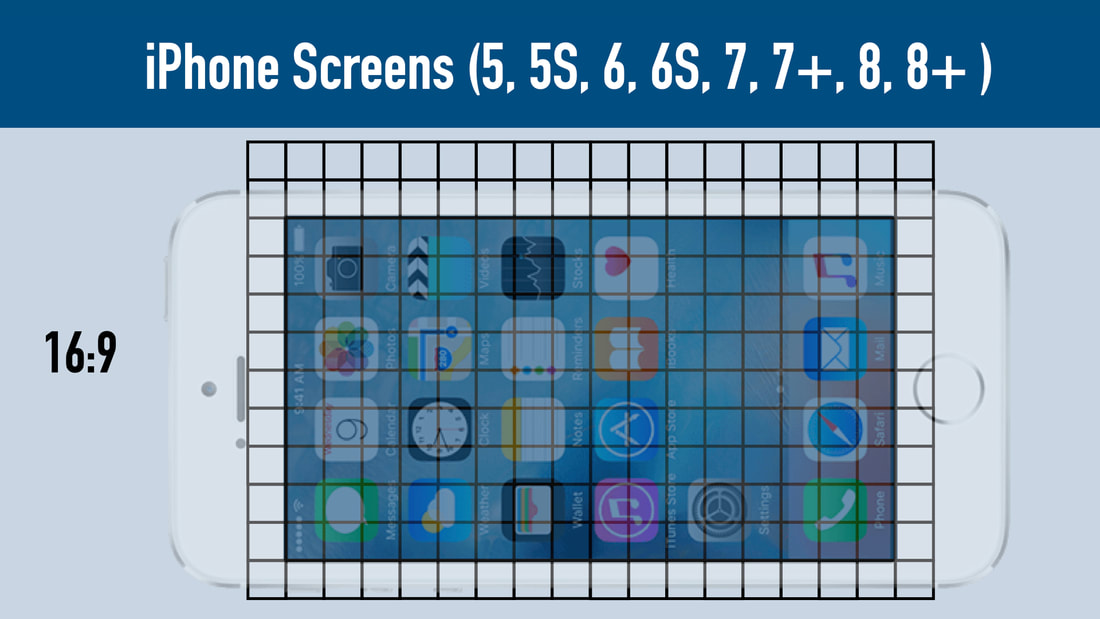

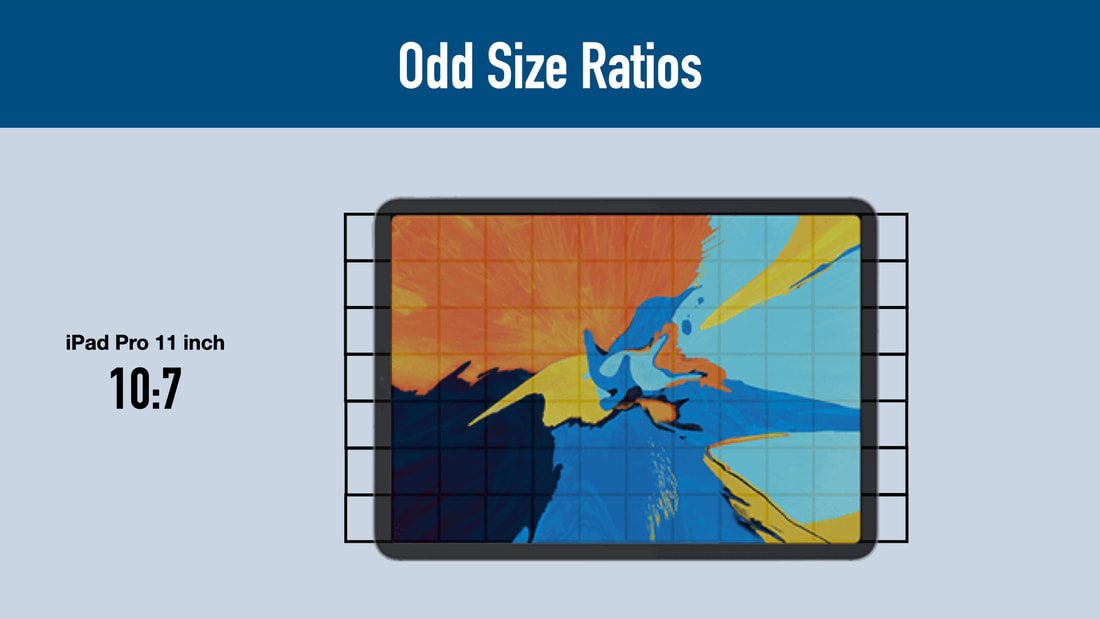

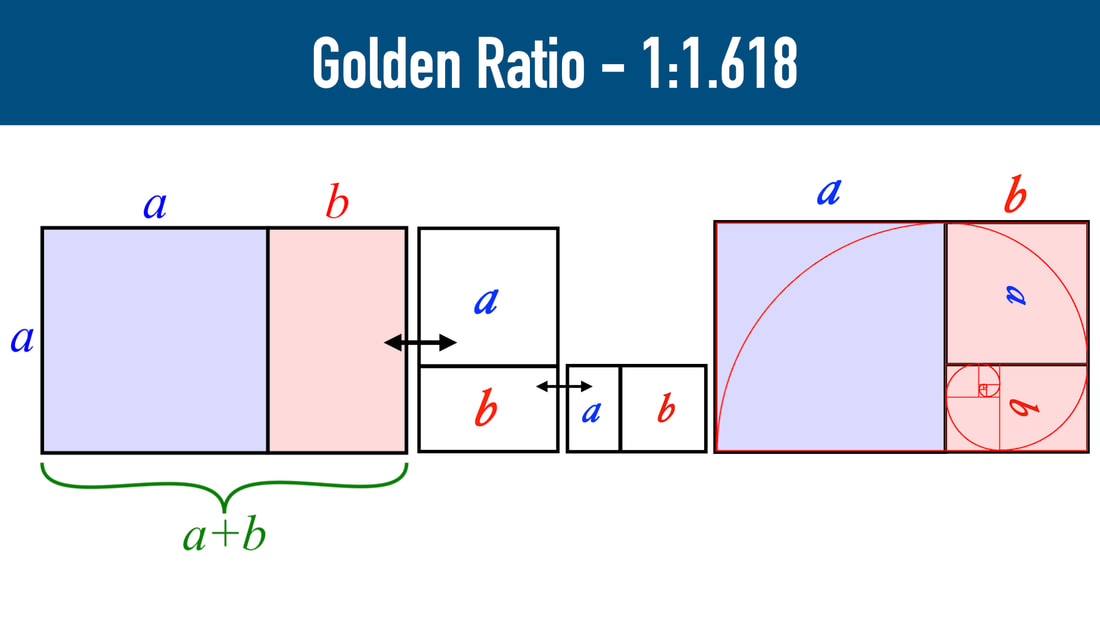

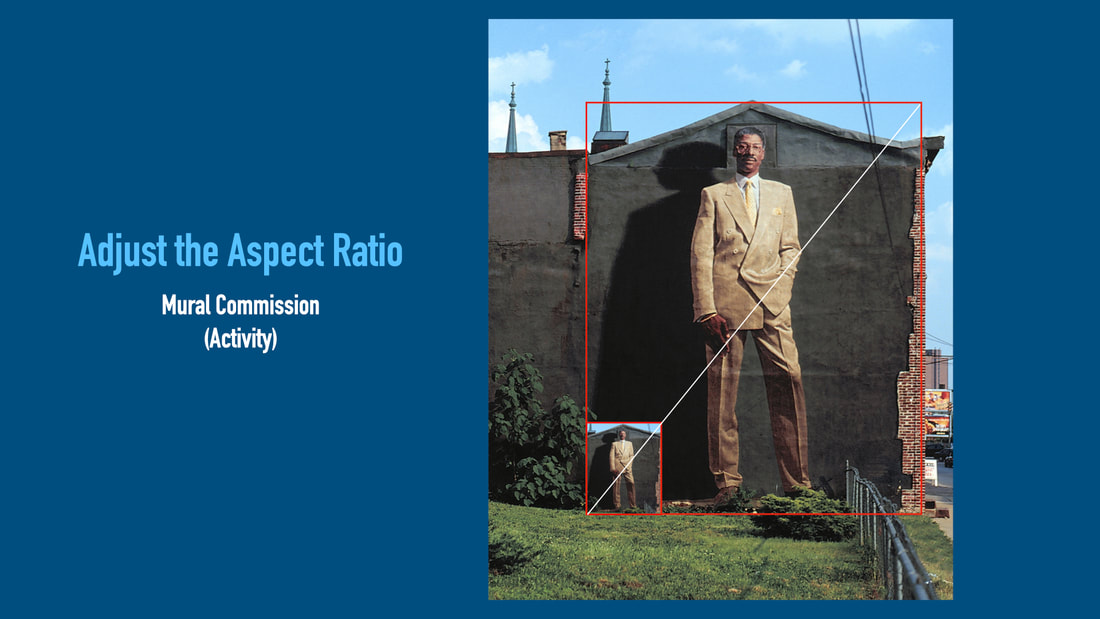

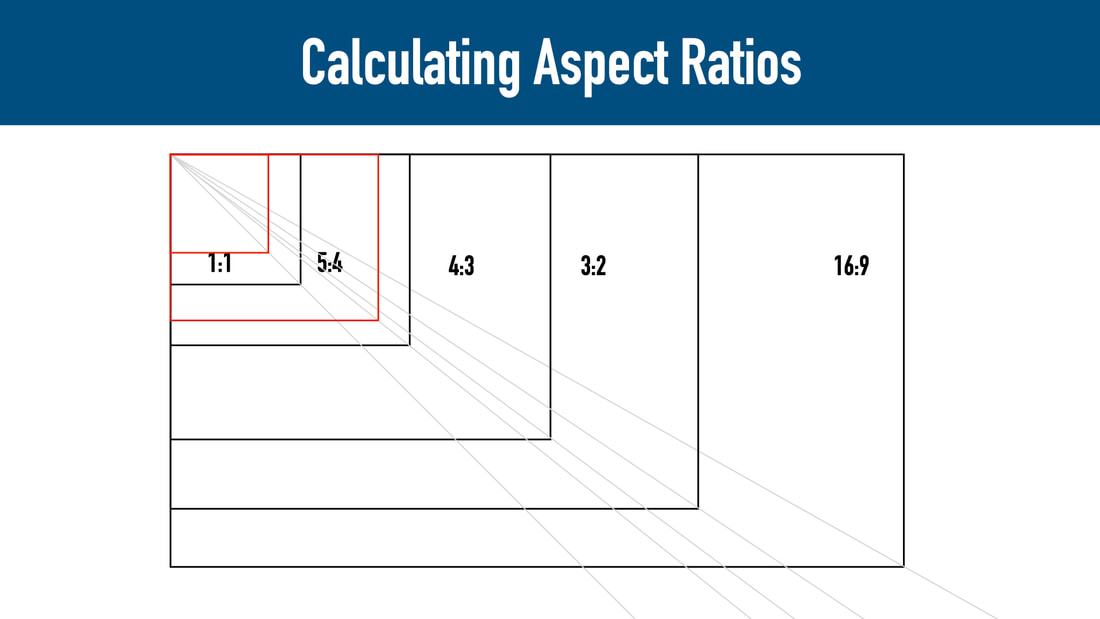

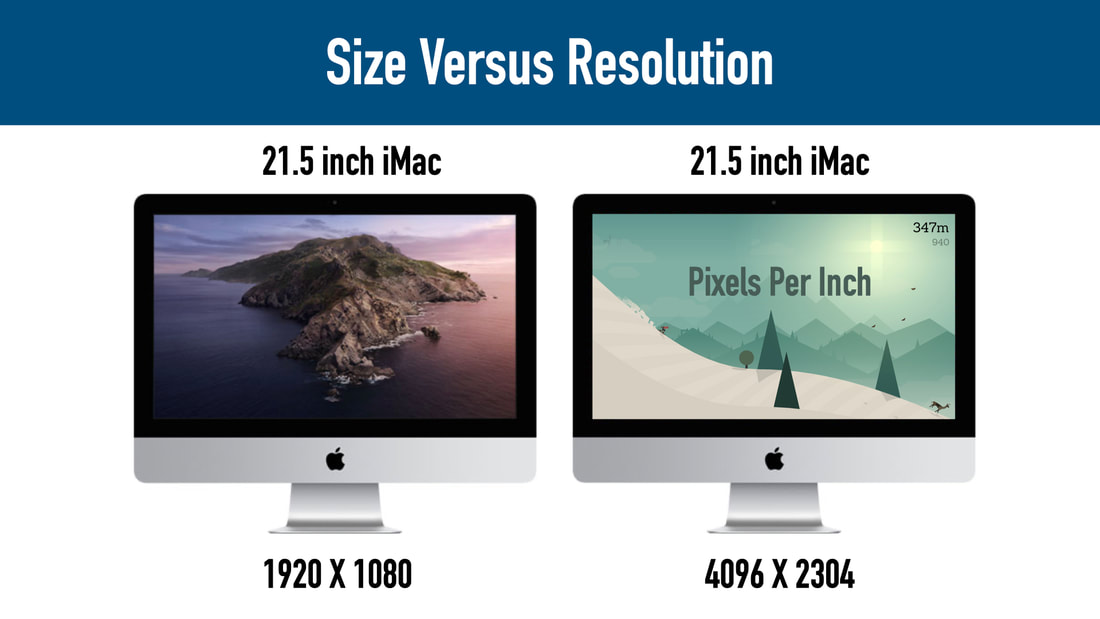

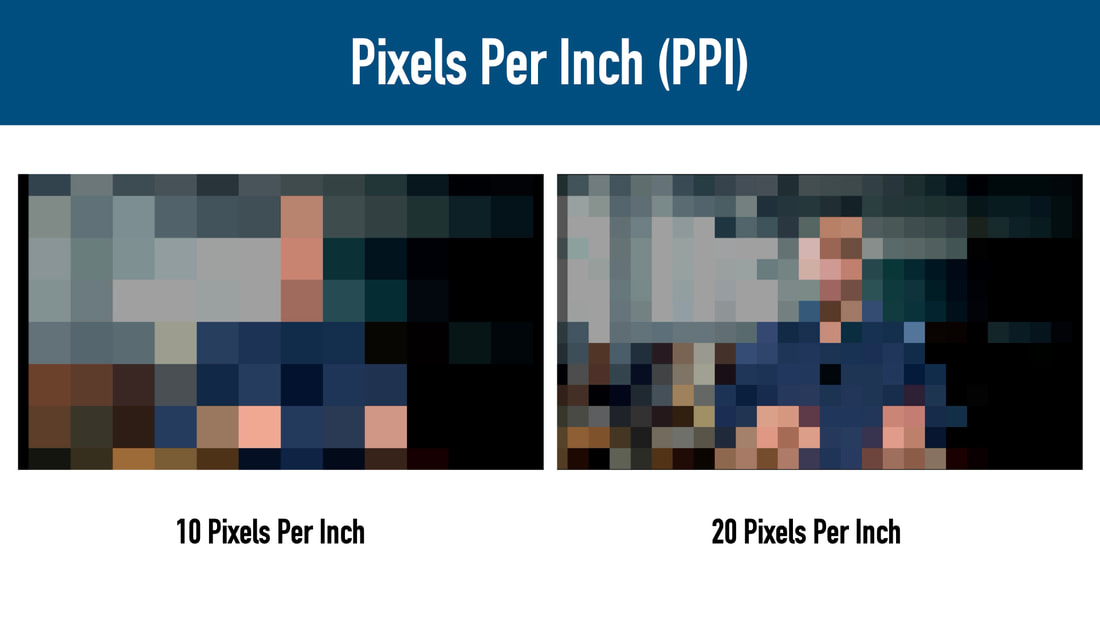

by Timothy P. Brown Aspect ratio is the proportional relationship between the width and height of a rectangle. Over the past century, mainly through the evolution of visual technologies, aspect ratios have become the windows through which we see things and experience world. Let’s explore the history of this phenomenon. Aspect ratios are usually written in the form of numbers separated by a colon: 16:9, 4:3, 3:2, etc. The numbers represent the width and height of a rectangle. Colons can be substituted for a dividing line 16/9 or decimals 1.77. These ratios can also be understood visually when viewed as squared units. The 1:1 aspect ratio featured above shows one unit as the height and one unit as the width, what we commonly understand to be a square. The 4:3 aspect ratio is 4 units across in 3 units down. Likewise, the 5:4 aspect ratio is 5 units cross and 4 units down. 1:1 Aspect RatioThe 1:1 aspect ratio was introduced in 1929 with the invention of the Rolleiflex camera. This unique twin lens camera produced photographs in the 1:1 aspect ratio (6 X 6), creating an aesthetic that would become iconic in the history of square formatted photography. Diane Arbus is one photographer who used this camera with very fine results. The camera was widely used by many, including famous people like Grace Kelly, Cary Grant, and the photographer, Richard Avedon. More recently, the popular social media platform, Instagram, revived this aesthetic by instituting the square format as an aesthetic standard for online photography (before Facebook purchased the company). Check out my post, “The Language of Instagram” for a more detailed study of this development. 5:4 Aspect RatioThe 5:4 aspect ratio was used during the early 2000s as a preferred format for computer monitors. Some videos were produced in this format for edge-to-edge viewing on these monitors. Coincidentally, the 5:4 aspect ratio was identical to 8 by 10 inch frames, a popular print format used mostly for portrait photography. 4:3 Aspect RatioThe 4:3 aspect ratio has a long history. It first appeared in the kinetoscope (1890s), which used 35 mm film. The kinetoscope allowed the viewer to see motion pictures through a peep hole, like the one example featured below called “The Kiss" (1895). Not surprisingly, this early example of filmmaking would influence the advent of television and the cathode ray tube, becoming the dominant aspect ratio for most of the 20th century. Computer MonitorsComputers are multifaceted, so it’s not surprising that monitors would appear in the same 4:3 aspect ratio. As CPU's expanded, resolutions increased to match their output, ranging from 640 X 480 and 800 X 600 to 1024 X 768 and 1600 X 1200. The iPadAnother fascinating use of the 4:3 aspect ratio occurred when Apple introduced the iPad in 2010. From its genesis to the current moment, the 4:3 aspect ratio appears in the 9.7, 10.2 and 12.9 inch iPad models. Considering the history and persistence of the 4:3 aspect ratio, Apple deduced that it would be perfect as a multipurpose touchscreen device. For example, the iPad allows you to do many things like watch movies, work on office documents, listen to music, play games, browse the internet, create art, and much more. Mobile PhotographyA significant shift occurred in our perception of the world when Apple decided to make the iPhone camera sensor a 4:3 aspect ratio. This development is important because it diverged from the standard 3:2 aspect ratio used in film cameras. The example below features a photograph taken with the original iPhone in 2007. The photograph tends to favor a square over a rectangle, creating a new aesthetic that would forever change how we see photographs. ProjectorsBefore HD monitors, it was common to use projectors to present content in the 4:3 aspect ratio. At this time, it was customary for PowerPoint and/or Keynote presentations to use this aspect ratio as the default size. Since projectors preceded widescreen TVs, images were projected by using a VGA cable or analog signals sent from your computer to a projector. The 4:3 aspect ratio is commonly referred to as the “standard” because of its widespread use over an extended period of time across a range visual mediums. 3:2 Aspect RatioPrior to mobile photography, the 3:2 aspect ratio was the standard for film photography. The 3:2 camera sensor in film cameras is wider than 4:3, allowing for an expanded viewing experience - one that some would argue is the ideal aesthetic for representing the pictorial world in landscape mode. Above is an example of a photograph taken with a Minolta film camera during a trip to Rome in 2006, a year before the iPhone was released. What is obvious is the extended rectangular format. When you compare it to the photograph taken with the iPhone (below), you notice a considerable difference in the way they capture horizontal compositions. The proportional relationship evident in the 3:2 aspect ratio can also be found in paintings. If you look at paintings produced throughout the history of European art, you will discover that many of them consist of compositions defined by the 3:2 aspect ratio. This is evident in paintings by Jacques Louis David, The Death of Socrates, 1787, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Claude Lorrain, Landscape with Merchants, c. 1629, National Gallery of Art, and Paolo Veronese, The Wedding at Cana, c. 1562, Louvre Museum. 16:9 Aspect RatioThe 16:9 aspect ratio is now the NEW standard for viewing widescreen videos. As the graph demonstrates, the proportional relationship is produced using units that are 16 across and 9 down. The shift is noticeable when you compare analog and digital formats. In the former, VGA cables were used to connect the computer to a projector, whereas HD monitors use HDMI cables to digitally transmit HD content using home entertainment devices like the Apple TV. Resolution and Screen SizesYou can also understand 16:9 aspect ratios in terms of the resolution found in videos, which range from 720p to 4K. The most common platform on the web for displaying 16:9 videos is YouTube. Exceptions include older films produced in the 4:3 aspect ratio, which YouTube will convert when older videos are detected. iPhonesiPhone screens, including models ranging from the iPhone 5s to 8 come in the 16:9 aspect ratio, no doubt due to the prevalence of widescreen videos. This development also anticipated a shift in presentation sizes, as widescreen formats for PowerPoint and Keynote gradually replaced the 4:3 aspect ratio we had become so accustomed to. Social media was impacted by the prevalence of the 16:9 aspect ratio, albeit, in manner that most professionals did not anticipate, and even detested. For example, the general consumer who is accustomed to using mobile phones to record video found it more intuitive to record videos vertically, rather than horizontally. Going from 16:9 to 9:16, the forever popular vertical format became the standard for social media platforms like Snapchat, Instagram, and, more recently, TikTok. Instagram even went so far as to create IGTV to acknowledge and celebrate the new video standard. Alternative Aspect RatiosThere are some aspect ratios that deviate from the norm, establishing niche markets. For example, the ultra wide 21:9 aspect ratio (2560 X 1080), is an alternative size for gamers who prefer a more immersive experience. We also see these exceptions in some of Apples devices, such as the iPhone Pro 11, which comes in a 19.5:9 aspect ratio and iPad models like the iPad Pro 11 which comes in the 10.7 aspect ratio. Golden RatioIn addition to these exceptional examples of aspect ratios, the golden ratio stands outside of technological developments, but represents a mathematical "ideal" for picture making. Theoretically, the ratio is the same as the sum of its two parts. In this visual example, "b" maintains the same proportional relationship as "a+b." The harmony that is evident in this proportional relationship has also been referred to as the Golden Spiral. The "golden ratio" is wider than 3:2, yet it offers an aesthetic ideal that is a nice alternative to the standard aspect ratios we use today. Calculating Aspect RatiosThere are simple ways to calculate aspect ratios. For example, if you begin with 630 X 1120 as a 16:9 aspect ratio, you can increase the size mathematically, while maintaining the aspect ratio (applications refer to this as "constraining the size." Divide the height (630) by the width (1120) or 630/1120=0.5625. Multiply this amount by a different size width (e.g. 1280), and you will arrive at the new proportional relationship, 630/1120 = 0.5625*1280 = 720, or 720 X 1280. Calculating Picture SizesVisual artists use similar approaches to mapping out pictorial compositions, especially when they are creating sketches in preparation for larger works like murals. If you want to try this on your own, draw a diagonal line from one corner to the other, extending it beyond the borders to create a larger dimension. The diagonal line ensures that you maintain the same proportional relationship (aspect ratio), while increasing the size (see diagrams below). Pixel DensityBy increasing the size and resolution, proportionately, you evidently produce larger screens. Yet, in terms of pixels, this does not necessarily correspond to an increase in size, but rather a stronger pixel density. In this example (below), Apple offers two versions of their 12.5 inch iMacs. One has a resolution of 1920 by 1080 (16:9), while the other has a resolution of 4096 X 2304. The latter has a stronger pixel density (Retina display), despite having the same size screens. This can be replicated in visual terms by drawing up grids that represents 10 pixels per inch and 20 pixels per inch. As the pixels increase or get smaller, the more clarity and brilliance is achieved. ConclusionSo in conclusion, aspect ratios are not merely mathematical formulas, but windows through which we view and experience the world. Whether you are making a painting on canvas, taking a photograph, recording video, creating digital art, or enhancing your productivity, aspect ratios are essential to how we experience and imagine the world.

2 Comments

The Black Lives Matter Movement captured the world’s attention following the killing of George Floyd by police. “Floyd’s last words “I can’t breathe” became a rallying cry for raising the public's awareness of systemic racism. This movement has become a pivotal time to address systemic racism, one hundred and eighty years after the civil war to end slavery, America’s primal scene of racial division. Yet, are museums prepared to address racism? The urgency to address racism is already beginning to take place at a few museums across the country. The American Museum of Natural History took down the racist statue of Theodore Roosevelt, and the director of the National Museum of American History, Anthea M. Hartig, issued a statement in support of the victims of police brutality, while providing historical context for racial violence in America. And recently museum staff members at the Metropolitan Museum and SFMOMA have begun to raise concerns about institutional racism. The time is right for museums to confront these issues and to do so on an institutional level. But what does that entail? Here is what I recommend:

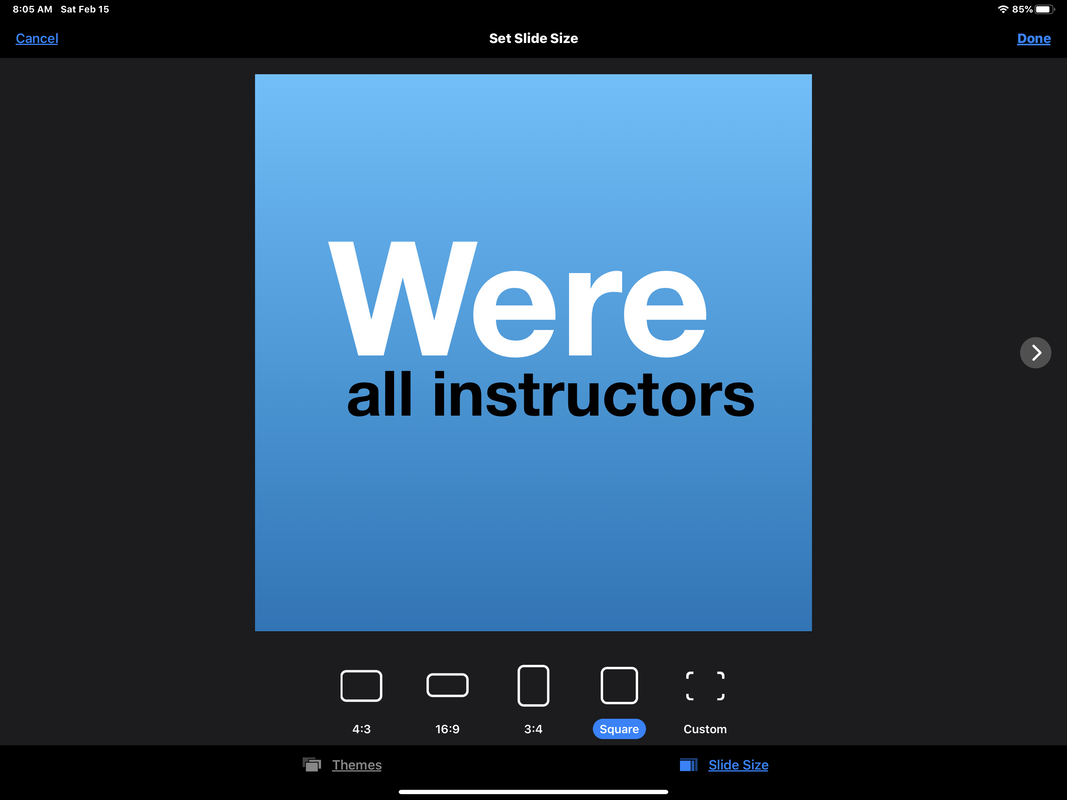

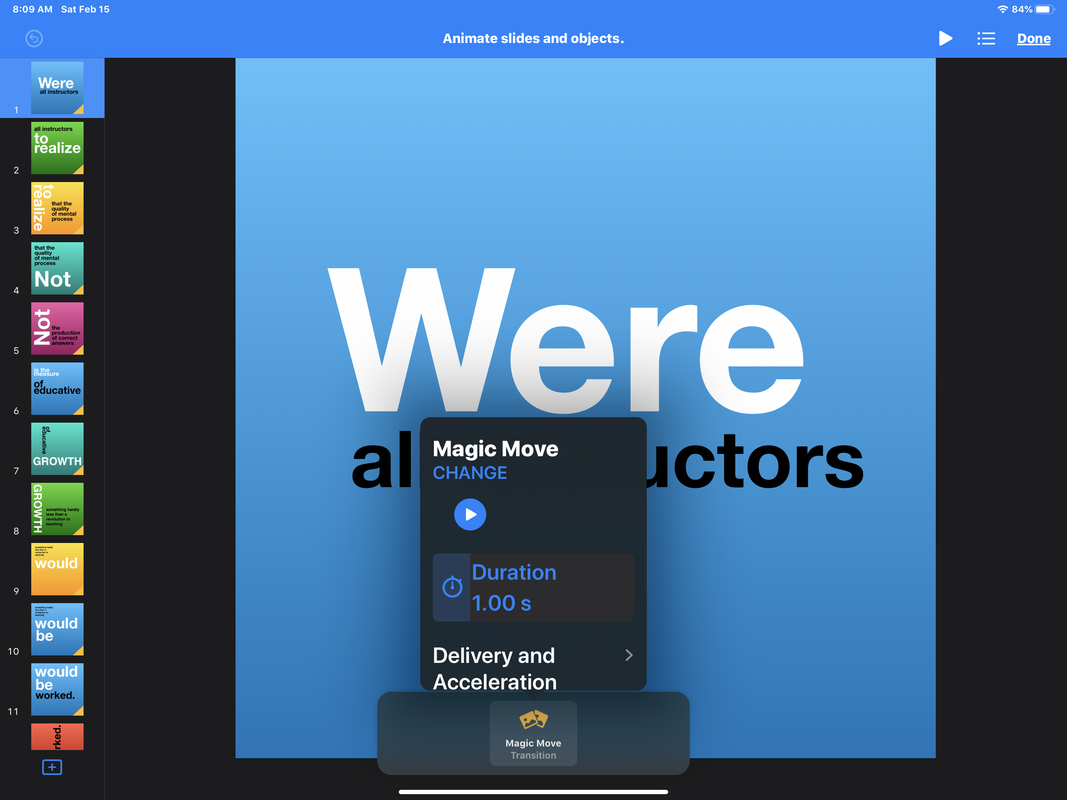

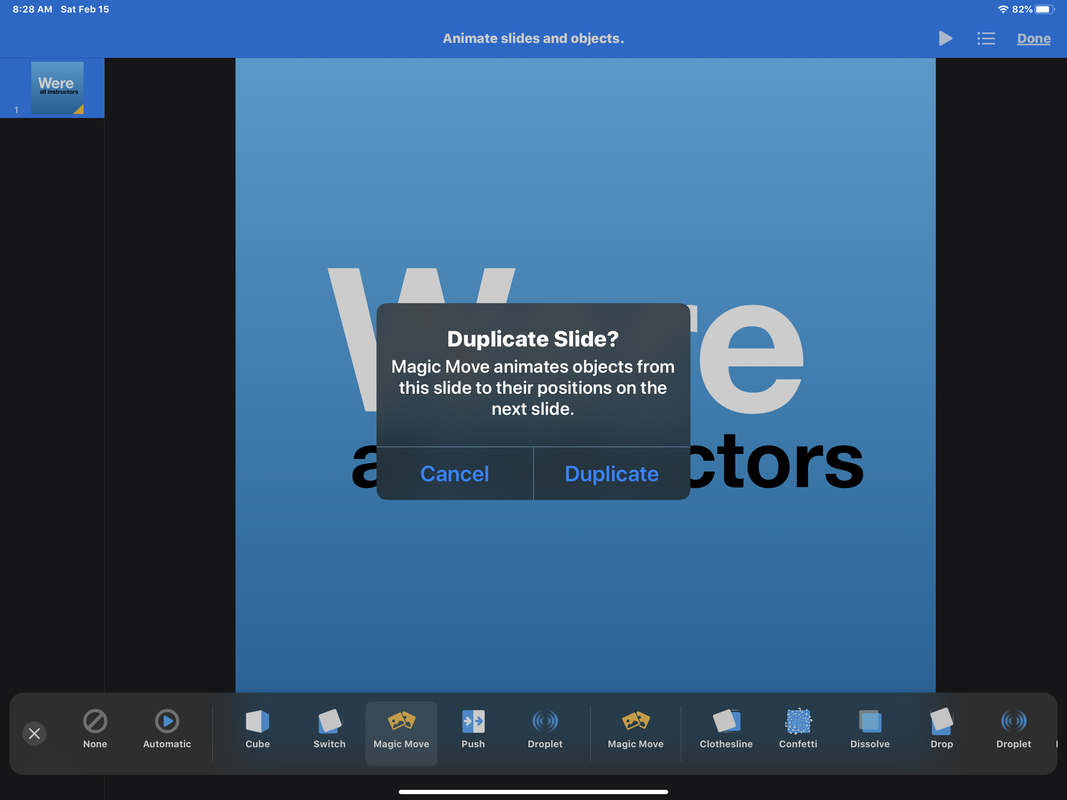

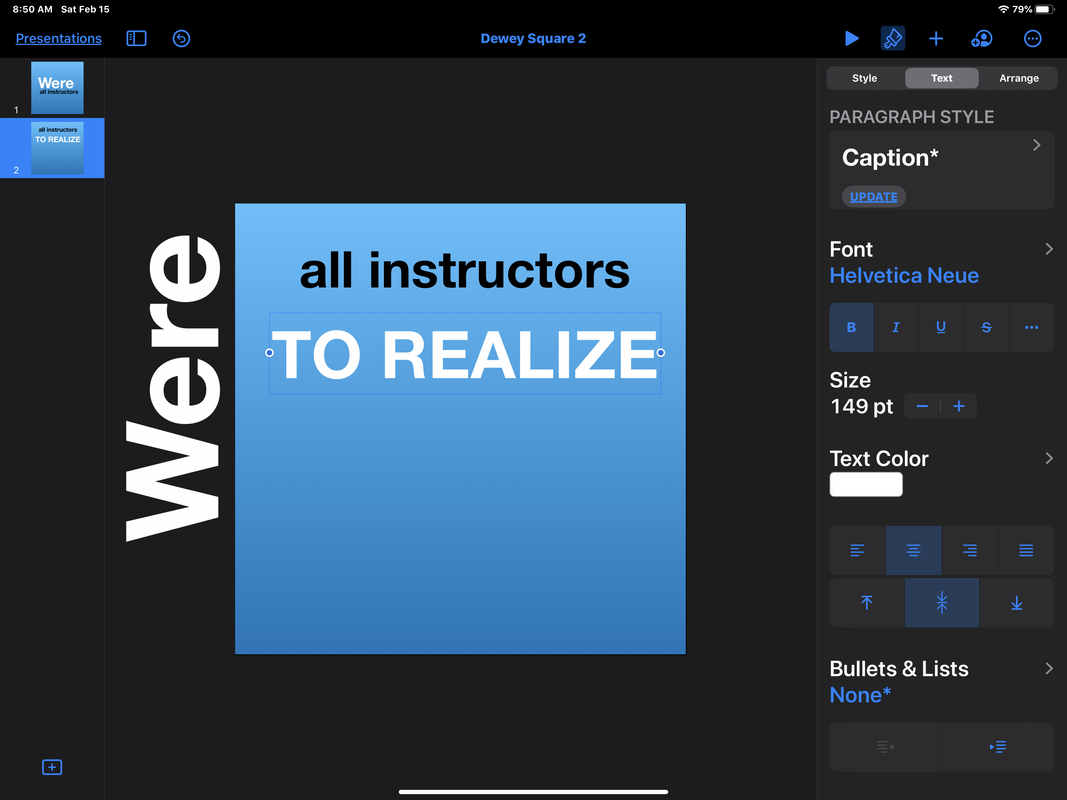

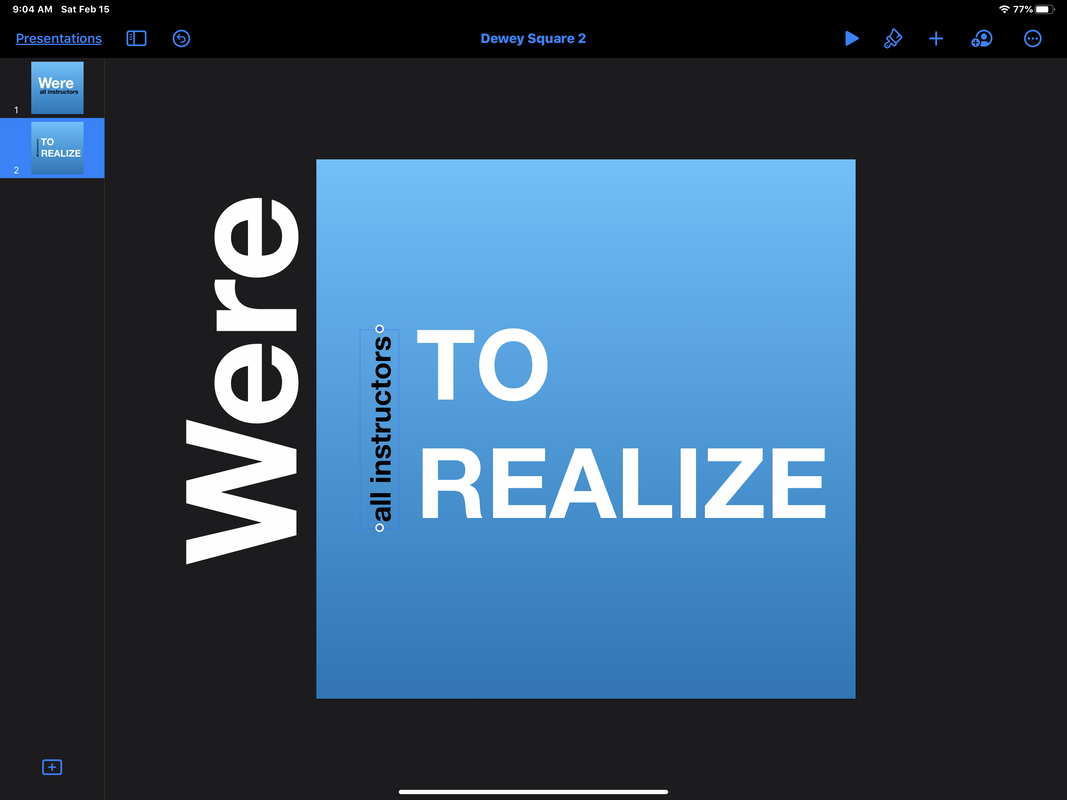

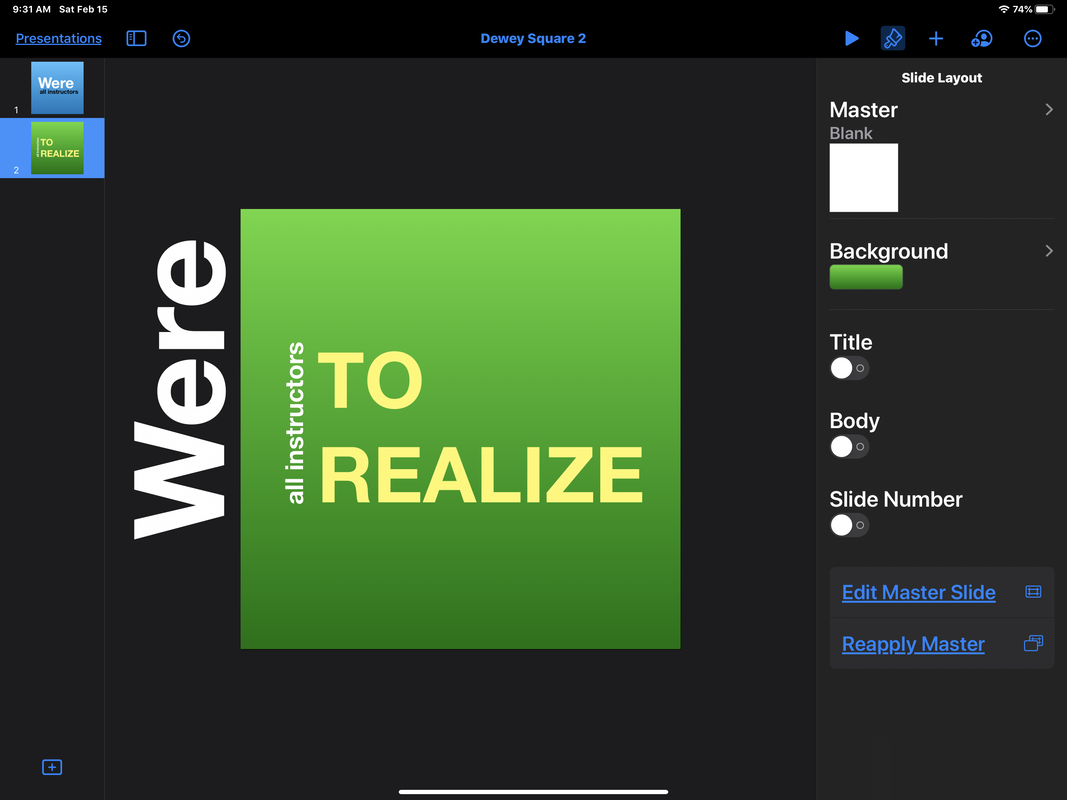

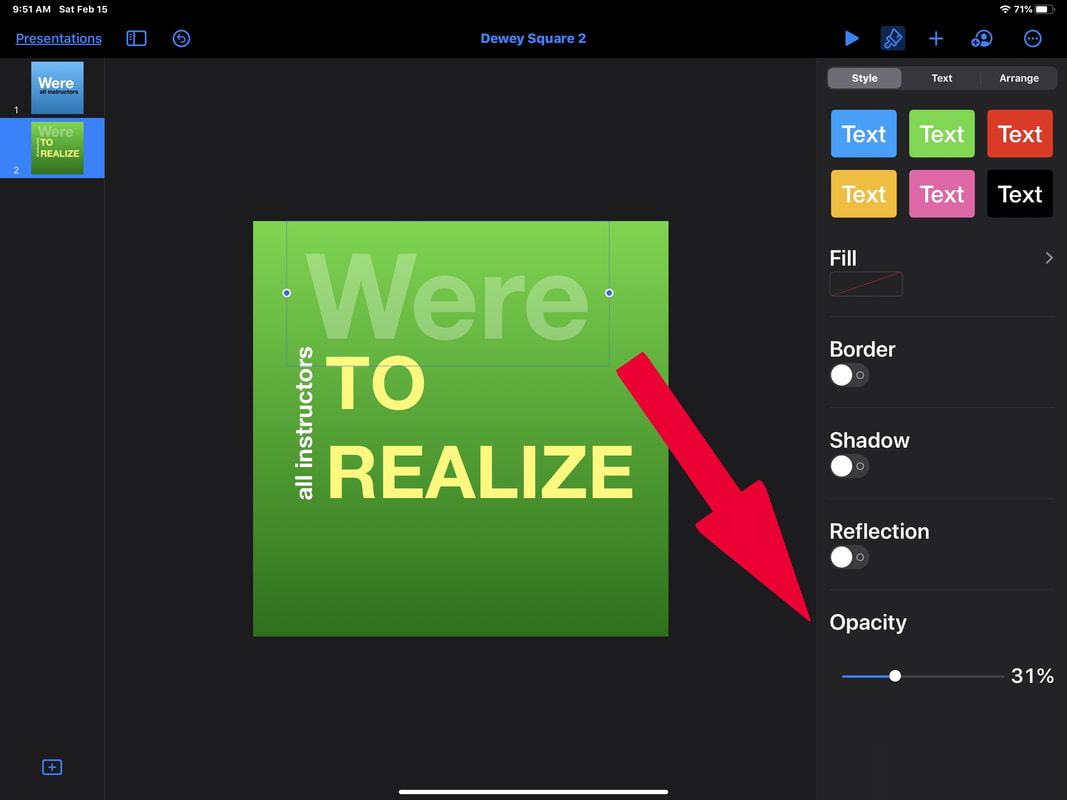

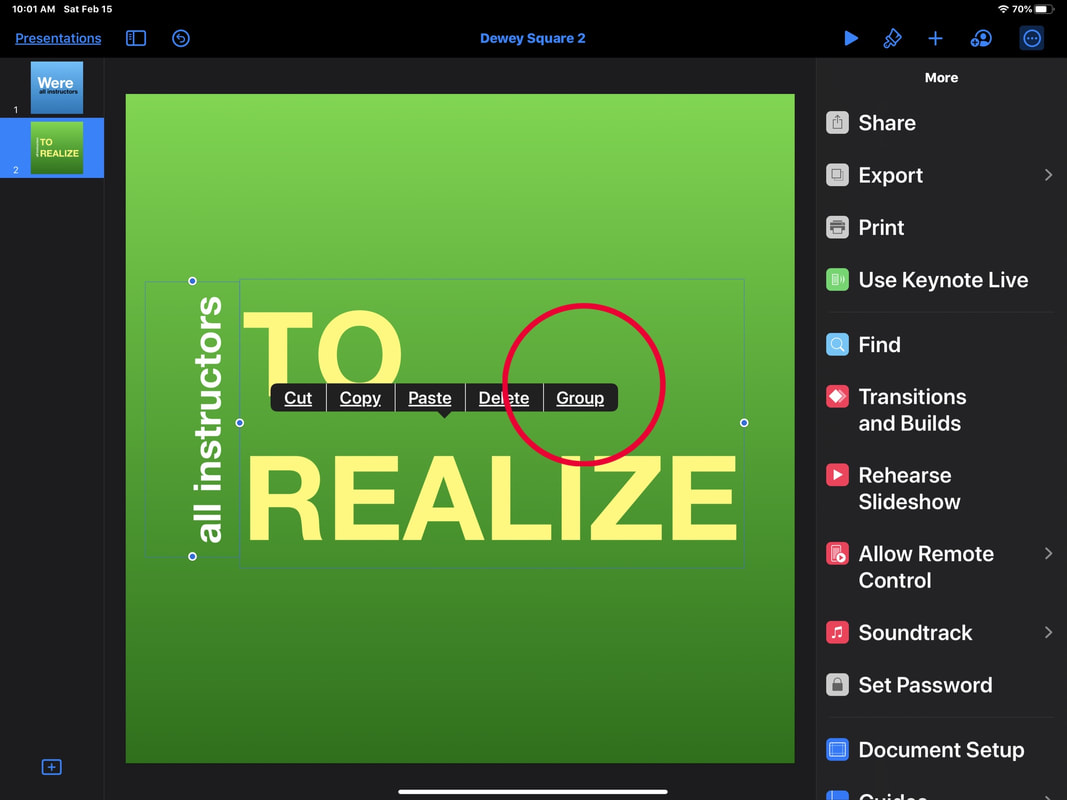

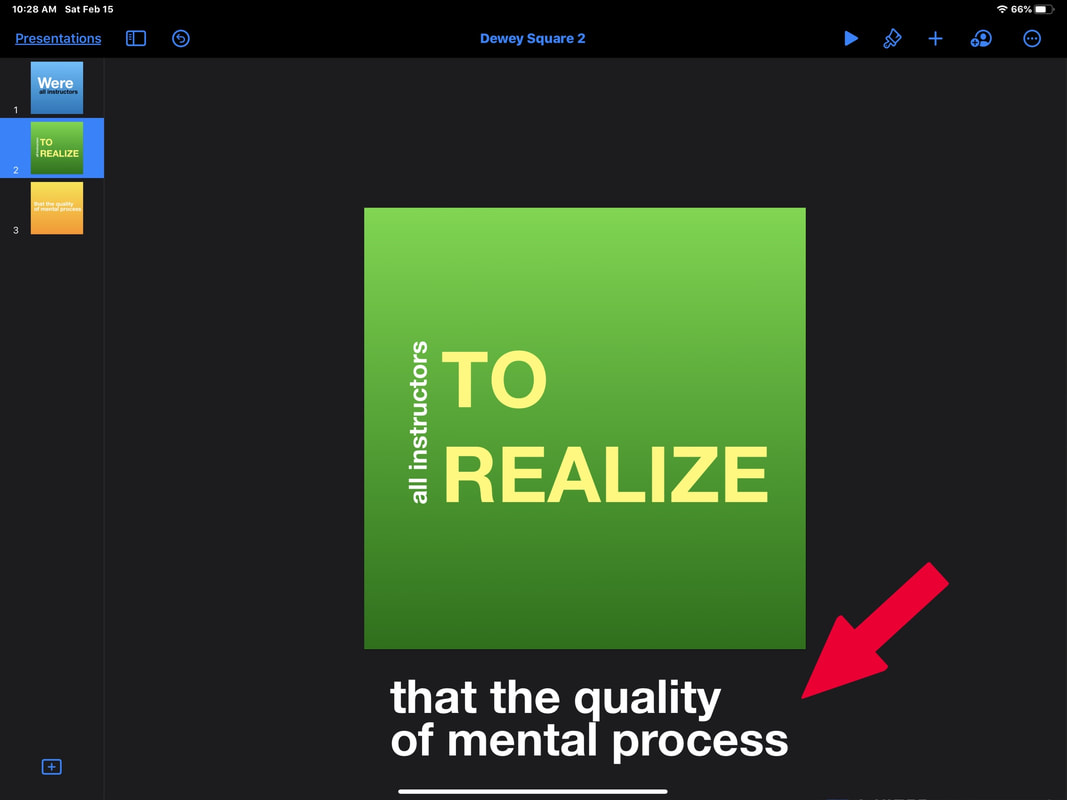

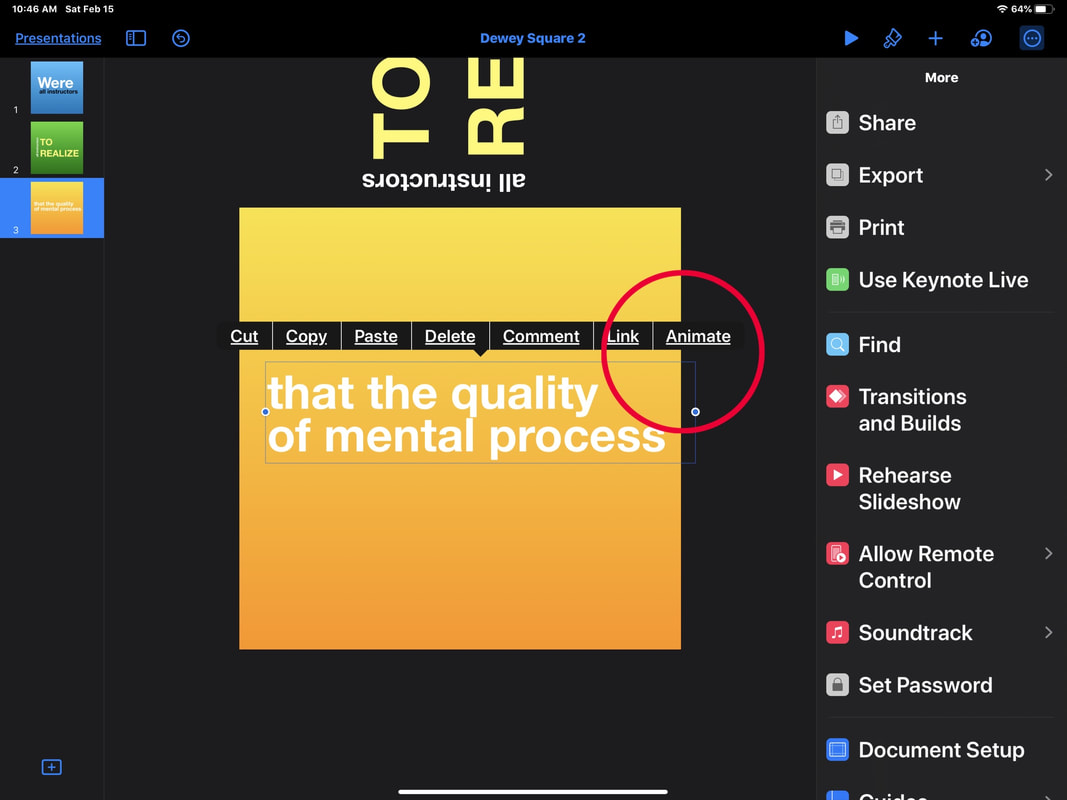

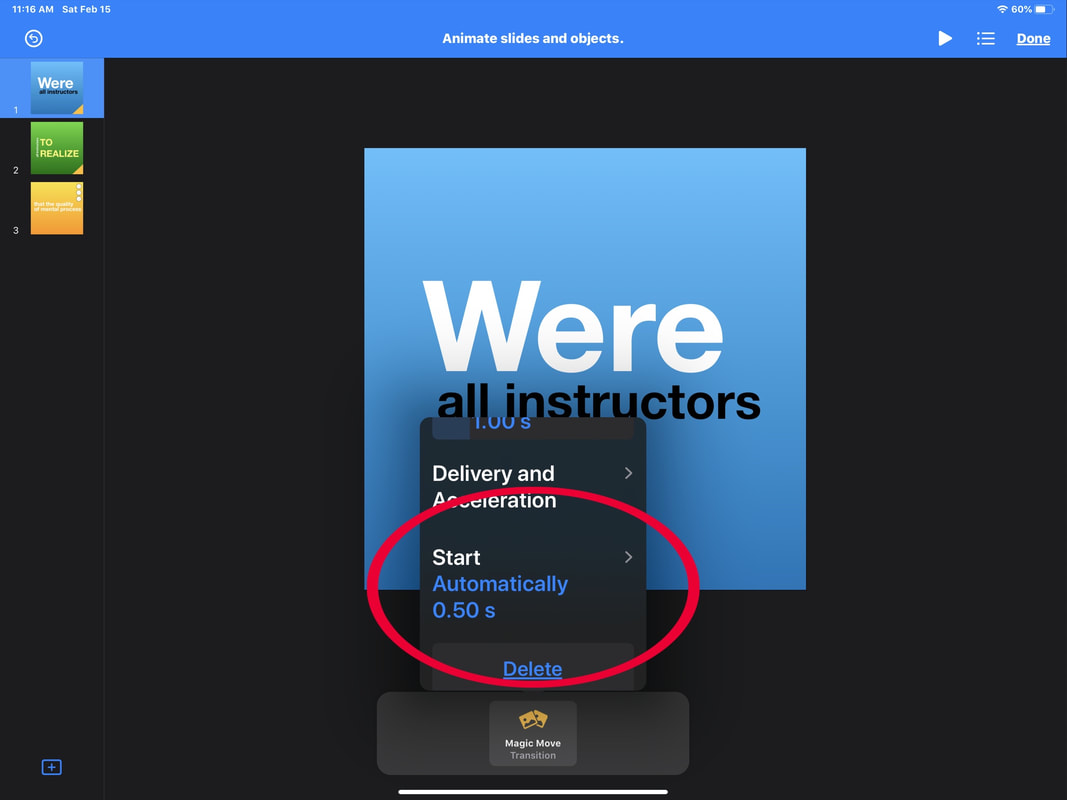

The Museum's mission statement is a powerful way to demonstrate a commitment to anti-racism because it defines the overall goal of the institution. A vision statement can outline a specific path to addressing racism and what the museum hopes to accomplish over a period of time. The most significant challenge for museums is to diversify staff by including more black people and people of color in leadership positions across the organization. The composition of the staff reflects the institution’s cultural values. The “culture” of the organization is a code word for race or maintaining a homogeneous organization. It’s hard to foster diversity and inclusion or show a commitment to anti-racism when museums are struggling on a basic institutional level to diversify the workforce. Other strategic decisions should also include the diversification of Museum boards. This is crucial because board members exercise a strong degree of decision-making power and can hold leaders accountable. In addition to staff and board members, museums must also demonstrate a commitment to diversifying exhibitions and collections that reflect the racial diversity of the community and the country. To effectively achieve this, museums must rethink how exhibitions and collections are installed and develop better relationships with Black artists who are willing to address racism and police brutality. This challenge is clearly reflected in a recent article about Shaun Leonardo whose exhibition on police brutality was canceled without being provided any explanation. In addition, museums should consider installations that deviate from linear progressions by exploring juxtapositions that encourage critical discussions about race and/or integrate interactive content to reflect how race is both present and absent in the ways we represent the world. Museum language is also a big obstacle to discussing race. Race neutral language that is used to title exhibitions or describe the content of work on display obfuscates and obscures the contributions of Black people in art, history, and culture, thereby perpetuating systems of domination and exclusion. The problem with language is likewise reflected in how museums choose to engage audiences on the web. Content that is featured online is often presented in a top down way which discourages feedback that may reflect varying racial viewpoints. For example, museum blog posts routinely disable comments to avoid public scrutiny. Most museums do a great job of offering educational programs to engage diverse audiences, but educators must explore ways to engage audiences, so that race is included in the discussion. Educators and docents must be comfortable with addressing conflict and difference in regards to race, and work to improve facilitation skills so that visitors can be engaged in a welcoming, inclusive, and nonthreatening way. It is important to emphasize that discussions about race do not constrain, limit, or deviate from objects on display, but help to expand the normalized discourse that occurs in museums. Otherwise, discussions about art, history, and culture will continue to elide and marginalize black people and people of color as problematic and less significant. What is evident is that museums prefer to play it safe. This makes it difficult for them to comprehend their role in the perpetuation of institutional racism and/or realizing the importance of getting feedback from racially diverse communities that challenge the homogeneity of a predominately white museum culture. Conclusion A lot of work needs to be done if museums aim to embrace a commitment to anti-racism and it will have to begin at the museum leadership level. In my next article, I will address my own experiences in the museum field and what I recommend as a “pedagogy of anti-racism” to make race and racism an integral part of the discussion. _______________ Timothy Brown, Museum Administrator, Educator, Digital Creator, Tech Blogger and Independent Consultant by Timothy Brown Keynote, a presentation tool available on the Mac, iOS, and iPad OS, is a great application for creating kinetic typography in presentations and videos. Start a New ProjectStart a new project by selecting a theme. Once you are inside the application you can change or customize the aspect ratio or size of your document. For example, on the iPad. select the three dots at the top right and select "document set up." Here you can select a "theme" or choose "Slide Size." The menu includes 4:3, 16:9, 3:4, Square or 1:1, and Custom. Magic MoveKeynote comes with a unique transition feature called "Magic Move." Magic Move allows you to re-position, resize, change color, and opacity of any element when you transition from one slide to the next. Tap the first slide of your presentation and select "Transition" and then "Magic Move.". You will be prompted to duplicate the slide. If you do not receive a prompt, duplicate the slide manually by tapping on the slide and selecting "copy" and then "paste" or by using the folio or desktop keyboard to enter command/D. Once the slide has been duplicated, you're ready to proceed. Change the positionBegin by changing the position of the text you duplicated from the previous slide. This step can include moving the text to another position, rotating the text, or moving the text outside the frame. As you do this, you can introduce additional words. Example:Change the SizeIn addition to changing the position, you can change the size or scale of your words. By using this option, you can de-emphasize words from the preceding slide while highlighting new words that you introduce in the next slide. Example:Change the ColorWith "Magic Move" you may also find it useful to change the color of your words. Similar to changing the size and position, by changing the color, you can give words an emotional quality. Color changes can also be applied to backgrounds. Example:Change the OpacityBy changing the opacity of your words, you can cause words to fade away or gradually disappear. This can be applied to words that are stationary or words you choose to re-position. By changing the opacity, you can vary the degree of meaning each word evokes. Opacity can be changed under the "Style" menu. In the example below, I adjust the opacity in the word "WERE" as opposed to moving it outside the frame. ExampleGroup WordsYou may want to consider the option to move groups of words at one time. You can do this by pressing and holding on one word and then selecting the other words until they are all selected. Or, you can select "group" from the dialog menu, if you want to animate the words as a group rather than individually. Below, "all instructors" and "TO REALIZE" are animated together as a group. ExampleAnimate New WordsBy default, Magic Move creates a smooth cross dissolve whenever you introduce a new word or phrase. The word gradually appears as the next slide is introduced. If you want to animate the word, add it to the previous slide, but place it outside the boundaries of the frame. In the duplicate slide, move it to the place where you want to appear. ExampleMagic Move + AnimationMagic Move is unique because you can transition between slides and animate individual elements within each slide at the same time. However, you can embellish your presentation with additional animations. For example, select a word in your slide you would like to animate and select "animate from the dialog menu. From here, you have build-in, action, and build out options. Since words can be animated by using "Magic Move" and "Animation," you can avoid confusion or ambiguity by choosing one or the other. Below is an example of how I use the anvil animation. Magic Move, however, gives your presentation a smoother flow. ExampleFinal ProjectsMagic Move in Keynote operates like a touch of magic. Elements move seamlessly into each slide adding flow and continuity to your presentations. Therefore, you have the ability to create professional projects as presentations and/or videos. If you are interested in the latter, make sure all slides are set to advance "automatically" rather than by tapping to advance. You can add sound to your presentation, although you have more flexibility on your Mac than your mobile device. Use the three dots or "more options" menu to export your project as a video. Create Your OwnKinetic typography gives added meaning to the words you present. You can enhance narratives, quotes, and commentaries in ways you cannot do with static words. Most importantly, you can use your own creativity to find original solutions to common themes or subjects. You can check out my final project below. For other examples of kinetic typography, check out this example of a quote by Stephen Fry.

by Timothy P. Brown The primary purpose of cinema is to make a subject dramatically interesting. Filmmakers identify situations or moments in time when people are confronted with a human or societal crisis and invite the viewer to experience them through imaginative identification. Law enforcement’s use of big data and policing technologies engenders similar conflicts, providing the substance for thoughtful analysis, and great cinematic storytelling. I have identified three films that address this topic in dramatic fashion: Enemy of the State, Minority Report, and, most recently, Anon. Each film identifies conflicts that drive the narrative, placing law enforcement and big data policing at the center of the conflict. ENEMY OF THE STATE (1998)“The only privacy that’s left is the inside of your head.” Enemy of the State(1998), directed by Tony Scott, is a spy-thriller that begins by identifying a conflict right away: privacy or national security. The opening scene takes place at Occuquan Park, Maryland, at 0645 hours, where NSA Security Advisor, Thomas Brian Reynolds (Jon Voight) and his team of NSA agents murder Congressman Phillip Hammersley (Jason Robards) who refuses to support the passage of the Telecommunications, Security and Privacy Act. The NSA agents use their access to national intelligence systems to uncover anything that may expose their clandestine operation. The agents intercept a telephone call from Daniel Zavitz, a nature photographer, who confesses to inadvertently recording the Hammersley murder through a motion-activated camera he planted in the park. Zavitz is tracked down by the NSA and dies in a traffic accident while trying to escape, but not before he runs into an old college friend, Robert Clayton Dean (Will Smith), an attorney from Georgetown. Zavitz placed the videotape inside Dean’s shopping bag, making him the NSA’s new primary target. The computational machinery that the NSA uses to track Dean’s whereabouts becomes the cinematic fuel that drives the subsequent action scenes. The NSA agents use tracers to track Dean’s cell phone, pager, shoes, watch, pants, and pen and satellite imagery to pinpoint his locations. Dean’s credit cards are canceled, he is fired from his job, his wife kicks him out of the house, and his friend, Rachel Banks (Lisa Bonet) is murdered. Dean’s life appears doomed until he meets his informant in an ongoing mob case, Brill (Gene Hackman). Brill (discovered later by the NSA as Edward Lyle, a formal NSA agent) reluctantly joins Dean in taking down the corrupt NSA agents. The film heads towards its dramatic conclusion when Dean manufactures a conflict between the mob boss, Pintero (Tom Sizemore) and the NSA who vie for possession the videotape. A gun battle ensues and multiple people are killed, with the exception of several “Ops,” a few restaurant employees, and Dean who later crawls out from under a table. The film concludes with Larry King’s newscast about the privacy act, and Dean’s wife Carla (Regina King) posing the question: “Who is going to monitor the monitors of the monitors?” MINORITY REPORT (1982)“Algorithms and big data models simply take inputs, Andrew Ferguson, How Cops Are Using Algorithms to Predict Crimes, Wired, (YouTube) Minority Report(2002) by Stephen Spielberg is a science fiction film that is set in Washington D.C and Northern Virginia in the year 2054. The conflict that drives the plot is predictive policing. Can the system prevent crime from ever occurring or is it tainted by bias and human flaws? The movie stars Tom Cruise, as John Anderton, Chief of Precrime, who uses an amalgamation of data to pinpoint where people are located and determines what day and time crimes will occur. The algorithms used to generate and compile the data are fictionalized in the form of three psychics or Precogs, who use their collective powers to see crimes before they happen. The Precrime department assures “that every American can bank on the utter infallibility of this system.” Captain Anderson, who has complete faith in the system’s accuracy, is challenged by Danny Witwer (played by Colin Farrell) who is sent to investigate the system’s effectiveness: John Anderton: “What are you looking for?” Danny Witwer: “Flaws.” John Anderton: “There hasn’t been a murder in six years. There is nothing wrong with the system, it is perfect.” Danny Witwer: “Perfect, I agree. But if there’s a flaw, it’s human. It always is.” A critical juncture in the film occurs when Captain Anderton confirms Witwer’s suspicions and discovers the existence of a Minority Report. The report includes inconsistencies noted in the Precogs pre-visions. A sub-plot is introduced that makes gender an important factor in the film’s development. One of the three Precogs is a woman named Abigail, the system’s most valued asset. Captain Anderton uncovers the truth about Abigail and confronts Director Lamar Burgess (Max von Sydow): Captain Anderton: “Hello Lamar,” “I just wanted to congratulate you. You did it.” “You created a world without murder.” “And all you had to do is kill someone to do it.” Abigail was the progeny of Ann Lively, a former “junkie” who later cleaned herself up and demanded to have her daughter back. Burgess kills Lively and stages two murders, one recognized by the Precogs as the “real” crime, and the other as an “echo,” which he knew the system would reject. The film ends by calling into the question the film’s essential conflict: Can predictive policing maintain its objective integrity or is it threatened by human motivation? ANON (2018)“What is the world coming to when our murderers don’t tell us who they are?” Anon directed by Andrew Niccol, is a futuristic sci-fi-techno-film that identifies anonymity as the central challenge that law enforcement faces to ensure absolute transparency. Building on some of the themes introduced in Minority Report, crime prevention depends on a pervasive system of surveillance that makes anonymity a threat to the social order. As detective Charles Gattis (Colm Feore) makes clear: “We rely on transparency. We can’t control what we can’t see. We require persistent identity.” In this high tech futuristic society, computational data is accessed through the mind’s eye of every citizen. The average person can view, share, upload, and exchange information (photos, memories, financial transactions), but law enforcement has special access to proxies and portals that allow them to access any past event. In the film, detective Sal Frieland (played by Clive Owens) is the main protagonist who is assigned to lead an investigation into a series of murders. The case is difficult to solve because the suspect is anonymous. The police department suspects a female as the murderer, the personification of “Anon” (Amanda Seyfried), otherwise known as “The Girl.” Law enforcement cannot detect her identity or her whereabouts because she has developed a sophisticated algorithm that erases the memory of those she meets. She is also capable of hacking the mind’s eye of others, forcing them to see what she sees, and erasing their personal memories. Frieland goes under cover as a wealthy stockbroker and hires “The Girl” to erase his memory of a Call Girl (Alyson Bath) - an encounter he purposely arranges in order to discover The Girl’s methods. Frieland inquires into her need to remain anonymous and she responds by revealing the irony of his question: “You invade my privacy, it’s nothing. I try to get it back, it’s a crime.” Gender, race, class and sexual orientation are some underlying layers that are slipped into the film, alluding to questionable motivations like bias. For example, a black man is shot while pulling out a bible from his pocket (mistaken for a gun); two lesbian women are shot in the midst of an intimate moment; and a black female house servant is accused (correctly) of stealing jewelry, but is ignored by detective Frieland because he is annoyed by the woman’s presupposed position of privilege. In spite of the fact that every location is documented by sophisticated mapping technologies, human beings still have the tendency to interpret the world subjectively and/or manipulate the technologies to produce less than objective outcomes. Male dominance in the law enforcement profession is also prevalent throughout, supported by the realization that the actual murderer is a white male, Cyrus Frear (Mark O’Brien), who manages to infiltrate the police department, while simultaneously hacking the The Girl’s algorithms and setting up an anonymous proxy. The tension between transparency and anonymity is maintained throughout the film, dramatizing the societal conflict between privacy and surveillance that seems virtually impossible to reconcile. CONCLUSION All three films, Enemy of the State, Minority Report, and Anon identify conflicts or a series of conflicts, and develop narratives that are dramatically interesting, forcing us with two plaguing questions that strike at the core of our societal beliefs: Are policing technologies flawless and factual or are they tainted by bias and human flaws? Is public safety a priority or is it privacy and individual rights? |

AuthorMuseum Educator and Tech Blogger Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed